Wednesday 11 October, 2017

Snapshots from Russia – 1956

Taken from: Scéal na Móna, Vol.13. No.49, December 2003, p.12-14

The second visit to Russia by a Bord na Móna delegation came about because the Russian Ambassador of the time, a Mr Maisky, had suggested that there should be an exchange of visits between representatives of the turf industries of both countries. It had been agreed after the first visit to the Glav-Torf industry in 1935 that a link between both organisations and countries be maintained, but obviously World War II had intervened.

The second visit to Russia by a Bord na Móna delegation came about because the Russian Ambassador of the time, a Mr Maisky, had suggested that there should be an exchange of visits between representatives of the turf industries of both countries. It had been agreed after the first visit to the Glav-Torf industry in 1935 that a link between both organisations and countries be maintained, but obviously World War II had intervened.

The 1935 visit to Germany and Russia was organised with the intention of tapping into valuable foreign expertise on the large scale industrialisation of bogland, but the 1956 visit to Russian was different, by then the Irish had gained valuable expertise of their own. As outlined by Todd Andrews in his autobiographical “Man of no Property”, by then: “Bord na Mona, the organisation responsible for the development of the turf industry, had been given the status of a statutory authority. Already it was producing machine turf at the rate of one million tons a year. It had one briquette factory [Lullymore] in full production and there were two more [Derrinlough and Croghan] on the drawing board. Four turffired power stations had been established, a peat moss factory [Kilberry] was producing for export and considerable progress was being made in the automation of bog operations. Above all the board had learned thoroughly the extremely difficult technology of bog drainage and it had found, at some expense, that without perfect drainage cheap turf cannot be produced in quantity”.

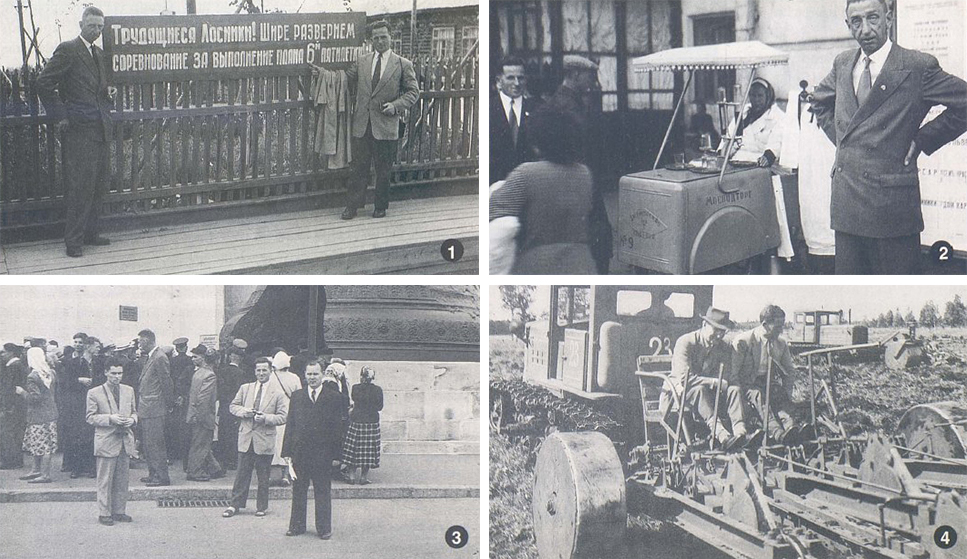

So the Irish delegation, Todd Andrews, Managing Director of Bord na Mona; Paddy Cogan, Deputy Chief Engineer, and Lewis Rhatigan, Manager of Boora Works, set out for the Soviet Union on this occasion having already experienced, in Todd Andrews’ words “a substantial sense of achievement” and until now we basically have been relying on the printed word to describe what they found there. Thankfully however one of them brought a brownie box camera with him and here we publish four of the images he captured. Amazingly these images would have surely been lost to posterity if Sceal na Móna hadn’t found a dozen faded negatives in a crumbled brown envelope in the corner of a box of miscellaneous material someone had given to Michael Jacob (formerly of Peatland World). The resulting photographs were the lost images of the Russian trip, and some were previously published in this magazine, but more importantly, some were recently used in the ESRAS produced “Nation Builders” documentary on Todd Andrews. The four images we produce here were interesting in that each taps into elements of the trip which required research to understand.

Photo No (1) shows Todd Andrews and Lewis Rhatigan beside a Russian sign which we believed was in a railway station, it may have been, but it’s a propaganda sign which translates as “The toilers of Losinka! Let us unfurl even wider the competition to execute the 6th five-year plan”. We are grateful to Vad Sologub, one of the country’s leading software engineers, and a friend of the editor, for the translation. Vad, who formerly worked on the Mir project, explains that the name Losinka (with a stress on the “i”) is derived from the word “Los” for an elk, so it was probably located somewhere close to woodland. Lewis Rhatigan, himself a committed socialist, obviously would have found empathy with the sentiments expressed in the sign.

Photo No (2) shows Todd Andrews, obviously in a quizzical mood, standing before a Moscow vending machine. Vad explains that the woman is selling water, on her trolley is written “MosVodTorg” which translates as “Moscow Water Sales Organisation”. She is actually selling a sweet soda water -Vad explains that inside her trolley there’s a carbonic acid gas cylinder, the gas is mixed with the water and issues from the tap as carbonated water.

Vad says that if you look closely you will see that one of the glasses stands on a pedestal-which is a glass-washer, by rotating the pedestal the vendor creates a water fountain inside the glass to wash it out. The two high cylinders in front of the vendor contain syrup, usually cherry and apple, which would be added to a customer’s glass on request. Vad adds: “I remember those vendors from my childhood. A glass of plain soda water cost 1 kopeck and one of single syrup 3 kopecks extra -a kopeck is 1/100th of a rouble, the photos brought memories of a great childhood filled with sweet water and ice cream”.

In Photo No (3) Andrews and Rhatigan visit a famous Russian Landmark, the “Tsar-Kolokol” bell in Moscow. Those of us who knew of the famous cracked “Liberty Bell” of Pennsylvania might not have appreciated that there was a much larger and even more historic “cracked bell” in Moscow. This Moscow bell is the last of four bells which bore the “Tsar-Kolokol” nickname, meaning “Tsar-bell” and all were cast from the same metal with additions.

The first bell, which weighed 35 metric tons, was cast by master bellcaster Andrey Chohov during the reign of Boris Godunov in 1559, but it was damaged by fire in the 17th century. Its metal was used in casting the second Tsar-Bell in 1624, during the reign of Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich. This time the master bellmaster, Emeliam Danilov, cast the bell right in the Kremlin, in the middle of Red Square, and the new bell weighed 128 metric tons. Happy with this major accomplishment the czar ordered that the bell should be mounted on a temporary bell loft to tryout its loudness. He ordered that all the bells of Moscow would be rung at the same time, but the sound of the giant new bell hovered over that of all the other bells and could be heard eight miles away. It may have had a hidden flaw however, or the two groups of twenty-five soldiers engaged in pulling the clapper back and forth became too ambitious, but it gave an uncertain sound, cracked and fell into pieces. The disappointed Tsar immediately ordered the casting of a new bell.

A year later the third Tsar-bell was cast in the same place by Alexander Grigoriev a 20-year old master, and the job took only six months (May through October). Now called the Great Dormition Bell, in honour of the Dormition Cathedral of the Kremlin, the new bell weighed 160 metric tons. It took ten years to install this bell in a temporary bell loft, and another ten before it was installed in a special constructed bell tower at the side of the tower called ‘Ivan the Great’. This third Tsar-bell was only rung on special occasions, with advance notice to residents, since it vibrations were akin to a small earthquake. It rang for 45 years, until another Kremlin fire made it fall down and crack in 1707.

In 1707 the Empress, Anna Ioannovna, gave the order to recast the leftovers of the third Tsar-Bell into a new bell, with the addition of 32 tons of new metal, bringing the weight of the fourth Tsar-bell to 220 metric tons. This work was entrusted to the master Ivan Motorin, who died after five years of preparations and an unsuccessful first casting. The job therefore fell to Mikhail his son who cast the bell successfully on his first try in 1735.

It is noteworthy that the whole casting process then took only 36 minutes with the molten metal flowing into the pit at the rate of almost 6 tons a minute. This last Tsar-Kolokol never rang however, while it was still in the pit a fire set the scaffolding above it alight causing the burning debris to fall into the pit. Well-meaning onlookers started to pour water over the bell to save it, causing it to crack and a big chunk fell off. For almost a hundred years the bell lay in the pit where it was cast until with great difficulties it was finally raised and place on a postament so that its decoration could be admired. It is now considered that it probably would have remained silent anyhow, since the vibrations it would have created would have damaged the buildings around it and its sound would have been one octave lower that the lowest key on the piano -a mere gurgle rather than a musical tone.

Photo No (4) shows Paddy Cogan (with the hat) and Lewis Rhatigan sitting on a rather unusual-looking bog machine.